Grounded Intelligence: How World Models Can Bridge Today’s AI and Physical AI

Feb 18, 2026

datadoo AI

Over the past year, whenever we talk seriously about what comes next in AI, we end up in the same place: today’s systems can talk about the world with surprising fluency, but they often struggle with the things that make intelligence usable in the physical world. The gap is not “more tokens” or even “more reasoning traces.” The gap is missing core ingredients: a grounded understanding of the physical world, persistent memory, and the ability to plan and reason about actions and consequences.

We are seeing a convergence around the same idea: we should shift toward world-based models that learn abstract representations of reality, objects, dynamics, and cause and effect, so systems can predict consequences under actions, not just predict tokens [1]. LeCun argues this is what enables planning, Hassabis ties it to learning physics from video [2], or Sutskever argues good prediction requires modeling the underlying reality [3]. The goal is not to guess the next token, but to anticipate what happens next in the world.

We find this framing useful because it lands exactly where the conversation about World Models and Physical AI is heading: the shift from systems that mainly describe the world to systems that can model it, predict it, and ultimately act within it reliably, safely, and at scale.

The Physical Data Bottleneck

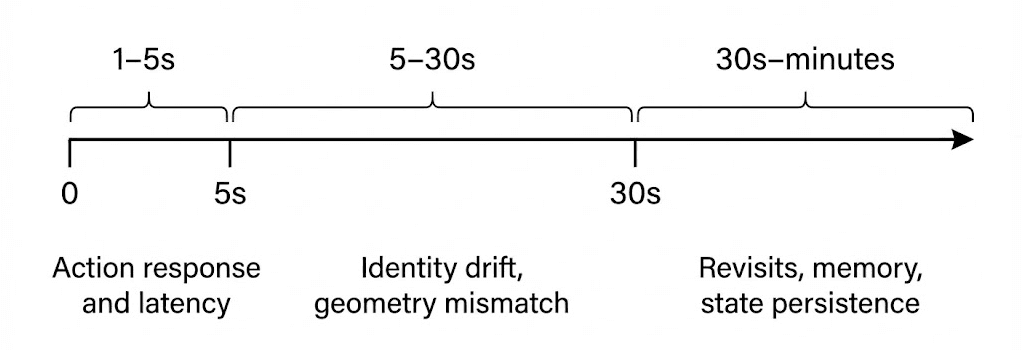

Across the robotics and Physical AI community, “physics-informed world models” rarely means a hand-written physics engine. The idea is broader: models that learn internal representations of objects and dynamics well enough to produce action-conditioned rollouts that respect basic physical regularities like persistence, occlusion, contact, and cause and effect.

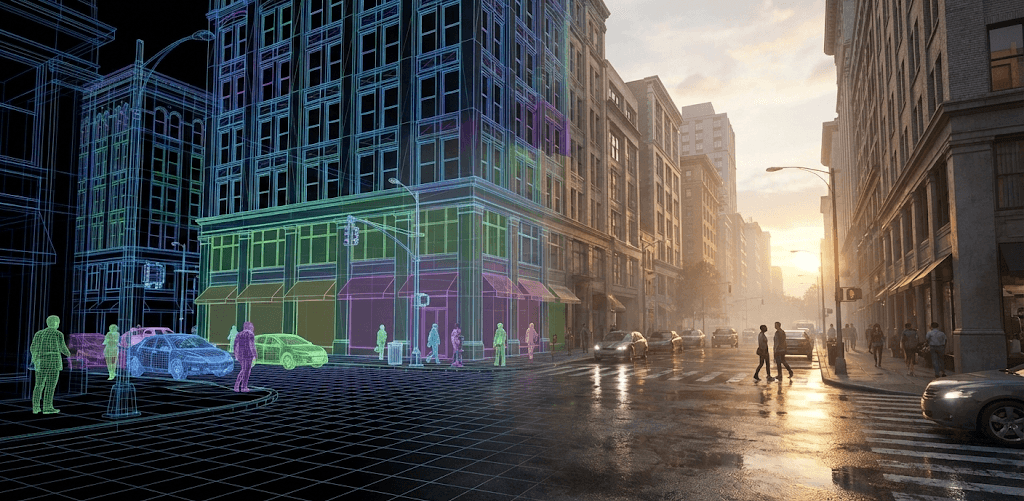

This matters because real-world physical data is painfully scarce in exactly the way ML hates: expensive, slow, risky, privacy-constrained, and still insufficient for the long tail (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Why real-world physical data is scarce.

So we keep arriving at the same conclusion: for embodied systems, scale comes from simulation. Either we build it painstakingly… or we learn it.

If we want robots and autonomous systems to get better faster, we need a way to create cheap experience, safely, at scale. NVIDIA has been unusually direct about this point in its Cosmos launch: physical AI models are costly to develop, require vast amounts of real world data and testing, and world foundation models can generate photoreal, physics based synthetic data to train and evaluate models [4].

And Jensen Huang has packaged the argument into a headline friendly claim: “The ChatGPT moment for robotics is here,” tying it specifically to world foundation models as a prerequisite for progress [5].

Whether we like the slogan or not, the underlying technical point is hard to avoid: without scalable world simulation, we keep bottlenecking on data collection, on rare edge cases, and on the cost and risk of exploration in the real world.

Two strategies for scaling experience

Once we frame the problem as a data bottleneck, the next question becomes practical: how do we actually scale experience for embodied systems? In the last year, we’ve seen two answers emerge in parallel. They’re not mutually exclusive, and in practice we may end up using both: Project Genie and Cosmos.

1) Project Genie: making “world simulation” tangible, interactive, and testable

Project Genie matters because it makes a world model feel concrete [6]. It is not just a paper metric. It is something we can steer. In the hands on reporting, the experience is described as real time 3D world generation you navigate with simple controls, but it comes with sharp constraints: 720p, about 60 seconds per session, and noticeable input lag [7].

After a couple of weeks in the wild, the community reaction has been fairly consistent: the concept is exciting, but the prototype reveals how hard the action loop really is [7]. The 60 second cap is tied to compute cost, and the interaction remains “somewhat limited” in dynamism, according to comments attributed to the team.

What do we extract from this for Physical AI?

Interactivity is the forcing function. Once users can drive the model, weaknesses show up immediately: latency, drift, limited action space. These are exactly the failure modes that matter for agents.

World sketching is a real workflow. Even if it is not a game engine, it is a way to spin up environments quickly, remix them, and probe behaviors. That is valuable for prototyping tasks, curriculum design, and rapid evaluation.

Edge cases are the prize. The same idea scales directly to safety and validation. We have already seen this direction in how DeepMind’s Genie 3 is discussed in simulation contexts for rare scenarios, where the value is not one perfect world but many plausible ones.

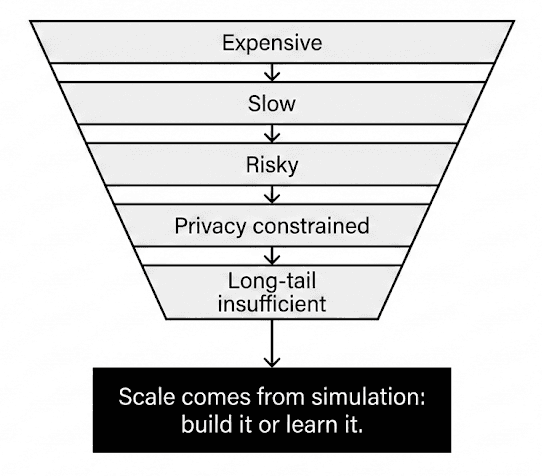

In short, Project Genie is a demonstration that learned world simulation can be interactive and accessible, and that interactivity is where truth leaks out. It surfaces the hard engineering problems that separate “pretty video” from “useful physical rollout” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Failure modes as horizon grows

2) Cosmos: turning world models into an industrial data and training stack

Cosmos takes a different route: treat world models as an infrastructure layer for Physical AI. NVIDIA describes Cosmos as a platform of generative world foundation models, tokenizers, guardrails, and an accelerated video processing pipeline built to advance autonomous vehicles and robots [4].

The practical takeaway is that Cosmos is optimized for the problems teams actually have:

Controlled synthetic data generation. Cosmos is positioned to generate physics based photoreal synthetic data and to support fine tuning for specific applications.

Structured conditioning as a feature, not an afterthought. Cosmos Transfer is explicitly framed around ingesting multiple modalities including RGB, depth, segmentation and more to produce controllable photoreal video outputs [8]. That is exactly the kind of controllability Physical AI pipelines need.

So where Project Genie teaches us about interactivity and human facing world sketching, Cosmos is an attempt to productize the world model idea into a pipeline that produces trainable, controllable experience at industrial scale, explicitly motivated by data scarcity in robotics and AV.

Both are pointing at the same north star: making experience cheap.

References

[1] Lex Fridman. “Transcript for Yann LeCun: Meta AI, Open Source, Limits of LLMs, AGI & the Future of AI.”

[2] Lex Fridman. “Transcript for Demis Hassabis: Future of AI, Simulating Reality, Physics and Video Games (Podcast #475).”

[3] R&A IT Strategy & Architecture. “What makes Ilya Sutskever believe that superhuman AI is a natural extension of Large Language Models?”

[4] NVIDIA Newsroom Jensen Huang quote: “The ChatGPT moment for robotics is coming…” Jan 6, 2025.

[5] NVIDIA Investor Relations (Press Release). “NVIDIA Releases New Physical AI Models as Global Partners Unveil Next-Generation Robots.” Jan 5, 2026.

[6] Google Blog. “Project Genie: Experimenting with infinite, interactive worlds.” Jan 29, 2026.

[7] The Verge (hands-on / reporting). “AI can’t make good video game worlds yet…”

[8] NVIDIA Newsroom (Press Release). “NVIDIA Announces Major Release of Cosmos World Foundation Models and Physical AI Data Tools.” Mar 18, 2025.